Jan. 22, 2009

BUDAPEST (JTA) -- The Yiddish expression "dos pintele Yid" is often translated as "the Jewish spark" -- an indestructible core of Jewishness that lurks deep within even unknowing or alienated Jews, ready to spring back to life at any unexpected moment.

The Forward's language maven, Philologos, once devoted a column to the term, describing it as an almost mystical notion.

"It posits that all Jews, even if they are unaware of it or have been raised so un-Jewishly that they do not know they are Jewish, have within them a Jewish essence that can be activated under certain circumstances," Philologos wrote.

Henryk Halkowski, who died suddenly on New Year's Day in his native Krakow, Poland, may have been one of the least mystical people I ever knew, but in many ways he embodied this concept.

A writer, translator and local historian, Henryk was like a pintele Yid for an entire city -- a city whose Jewish population of more than 65,000 had been all but wiped out in the Shoah. A city where only some 200 or so Jews live today.

To my mind, Henryk was one of the most noteworthy personalities in the new Jewish reality that has emerged in Poland since the Iron Curtain came down nearly 20 years ago.

"He was a guardian of Krakow's Jewish legacy," said Joachim Russek, director of the city's Center for Jewish Culture.

Born in 1951 into the echoing vacuum of post-Holocaust Poland, Henryk was haunted by the ghosts of Krakow's Holocaust dead and the generations of Krakow Jews who went before them.

He, in turn, haunted Jewish Krakow, learning its secrets and becoming so intimately attached that he seemed to have real, psychological difficulty leaving the city even for a few days.

"He was a character," said Stanislaw Krajewski, a leader in Poland's Jewish revival and the American Jewish Committee representative in Warsaw. "He was so Cracovian -- a Krakow curiosity."

With his encyclopedic knowledge of Krakow's Jewish history, culture, legend and lore, Henryk became a touchstone for me and other Jewish foreigners who began trickling in to Krakow in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

"For many of us, Henryk Halkowski was one of our first significant encounters with Krakow, and for all the years thereafter he remained a fixture of its character as much as any other person or institution," said Michael Traison, an American lawyer who has worked for years in Poland and sponsored many projects aimed at preserving Jewish heritage and fostering Jewish revival.

A stocky figure with thick glasses and a gray-flecked beard, Henryk was a familiar figure in Krakow's Jewish quarter, Kazimierz, where he roamed the streets with a restless energy.

"Wherever one walked in Kazimierz, regardless of the time of day or night, you couldn't help but run into him, then have a drink, then have a meal," recalled the klezmer musician and filmmaker Yale Strom, who met Halkowski in 1984 and featured him in several of his documentaries.

I first met Halkowski in the early 1990s.

Back then Kazimierz was a slum, a dilapidated ghost town that still showed the scars of Nazi mass murder and communist oppression.

Henryk, as head of a Jewish club, had formed the nucleus of a group of younger Jews who had attempted to revive Yiddish culture in the 1980s.

He recalled to me how foreign Jews often seemed uncomfortable meeting younger Jews in Poland -- how they couldn't understand their desire, or need, to remain.

"American Jews have a stereotype about Polish Jews who stayed here," he told me. "It's as if we are seen as 'traitors' to the nation."

In the years since then, Kazimierz has grown into a lively tourist center, with Jewish-style cafes, renovated synagogues, kitschy souvenirs and constantly milling tour groups.

The district has a resident rabbi and a Chabad center, and there is a plethora of Jewish cultural and educational institutions -- even a local Jewish publishing house, which has brought out Henryk's own books.

Henryk was an acute observer of the transformation, even as he became one of its protagonists.

"Disheveled and in disarray, he never disappointed as he cynically critiqued the absurdity of the Disneyland display of Jewish heritage and tragedy," Traison said.

"Orally and through his writings, he offered a sincere and unique insight into Cracovian culture and specifically that special Kazimierz life created since the fall of communism.

"Henryk remained and remains a genuine part of that milieu," he said. "And if one word is needed to describe him that is it: genuine."

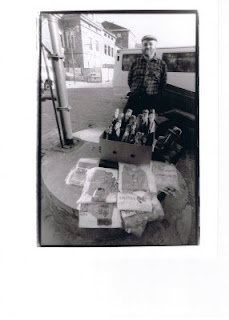

In 1997 I took a picture of Henryk, a wry grin on his face, as he posed a trifle awkwardly at a Krakow souvenir stall selling T-shirts and carved wooden figures of Jews.

"Shall I tell you my obsession?" he asked me once, as he tucked into a bowl of chicken soup and kreplach at one of Kazimierz's trendy new Jewish-style restaurants.

"What we need in Kazimierz is some sort of institution that presents Jewish life as it really was here. What an apartment was like, for example; what a cheder was like, what a workshop was like. How the people here really lived. Something to inject a bit of reality into the gentrification."

Henryk was buried in Krakow's Jewish cemetery. Some 300 people braved the snow and bitter cold to pay their last respects. Rabbis and cafe keepers alike mourned at the graveside.

I could not make the trip to attend. But I remembered what Henryk had told me years ago, during one of our earliest conversations.

"Kazimierz," he said, "can be a place where meaning can be materialized."

That still holds true. But it simply won't be the same without him.

Real Full JTA Story